The Only Free Lunch?

“Diversification is the only free lunch in investing,” or so goes a saying attributed to Nobel Prize-winning economist Harry Markowitz. If only! The purpose of owning a diversified portfolio is to accumulate wealth more steadily and with less drama: lower day-to-day volatility and shorter, shallower draw-downs. But if diversification was free, most investors would hold well-diversified portfolios. [Narrator: they do not.] In fact, diversification does have a cost: the cost of being different.

Diversification does have a cost: the cost of being different.

By definition, a portfolio’s performance always lags that of its strongest asset. Therefore one cost of diversification is the regret of missing out on the highest returns of the day. Hindsight can be cruel. A diversified portfolio will hold assets which zig when others zag, so the investor who monitors her investments closely will see red mixed in with the green. Diversification means always having something to be sorry about: sorry about the assets we own in preparation for the thing that hasn’t happened yet, hasn’t happened lately, or may never happen.

A well-diversified portfolio should perform in good economic times, but should also be able to weather recessions and prolonged bouts of inflation. Both are inevitable, but conventional portfolios aren’t built for them. A well-diversified portfolio should help an investor survive financial shocks, which happen more often than theory would predict.

In 2022, stocks and bonds both suffered substantial losses. This was a novel experience for most investors, who've been told they own a diversified portfolio. In fact, there are many reasons to question whether a portfolio of stocks and bonds will provide adequate diversification in the future. We've lived through a “golden age” for conventional portfolios, including the ubiquitous 60/40 combination of stocks and bonds. The multi-decade period of disinflationary growth from the early 1980s boosted the returns of both asset classes and provided a consistent source of diversification: when stocks stumbled, interest rates fell (bond prices rose) in the expectation of monetary policy easing from central banks. Viewing history through a wider lens, we expect lower returns for both asset classes and for their prices to move more often in the same direction. In other words, conventional portfolios should provide less diversification going forward.

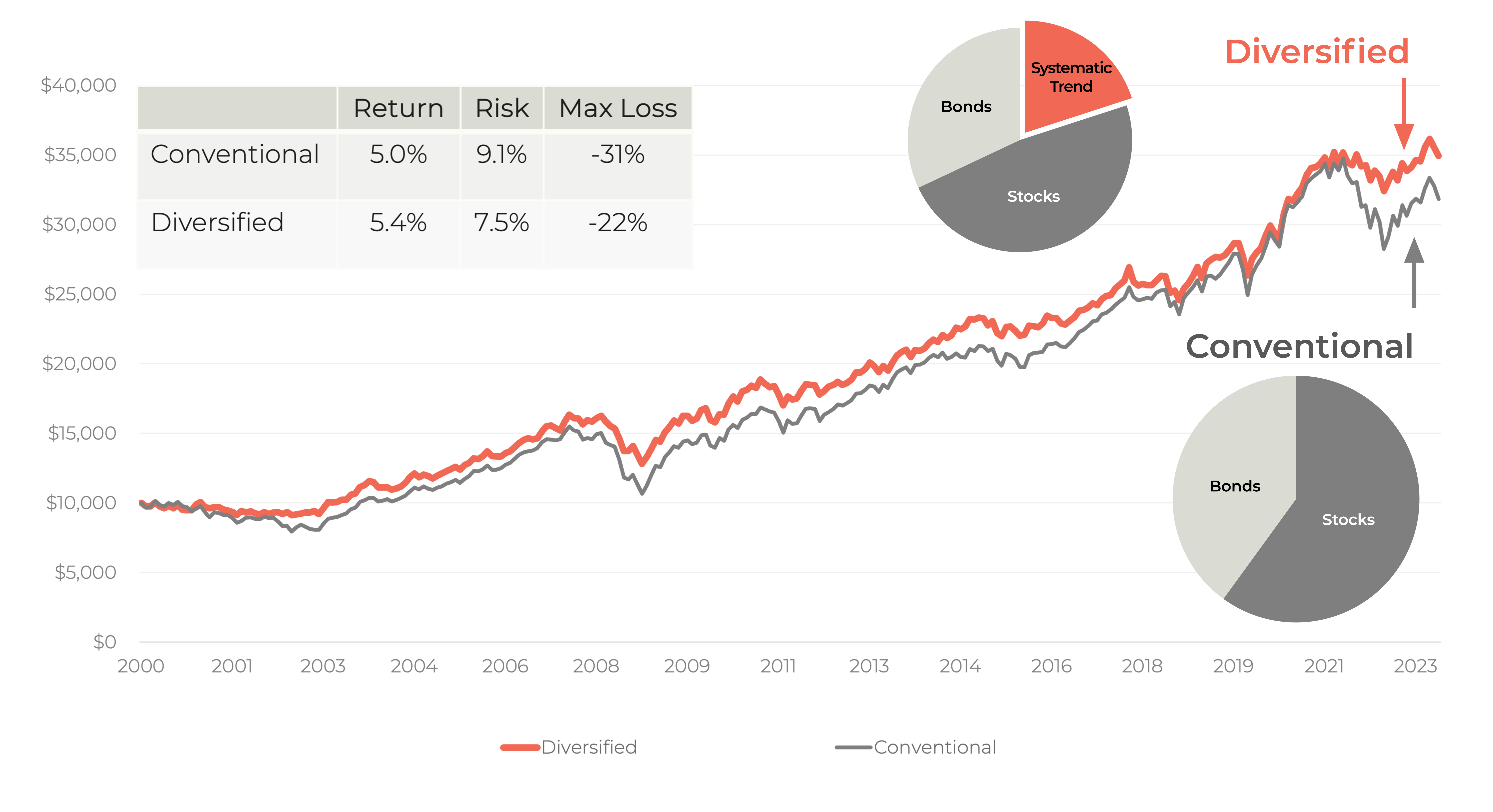

How can we build a better portfolio? One way is to own assets that provide better diversification: delivering positive returns when the rest of the portfolio is under stress–assets that zig when a conventional portfolio zags. A perfect example is a strategy we’ll call Systematic Trend.1 Had we carved out part of a conventional 60/40 portfolio and allocated 20% to Systematic Trend, we would have enjoyed higher returns, lower volatility and shorter, shallower drawdowns–notably during major shocks to the financial system: the aftermath of the Dot-Com boom, the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-9, and COVID-19.

Now past performance is no guarantee of future returns, but how could we (with hindsight) not prefer this alternative? For one reason, the diversifying strategy we added will be unfamiliar to many investors–and to many advisors as well (despite allocations of over a half trillion dollars of institutional capital!). Assuming advisors do understand the strategy, they must accept the burden of explaining it to clients and justifying its idiosyncratic performance. Due to availability of index data, we’ve examined the period starting in 2000 for this illustration, which was far from stellar for Systematic Trend, including 6 years of flat performance during which global equities nearly doubled.

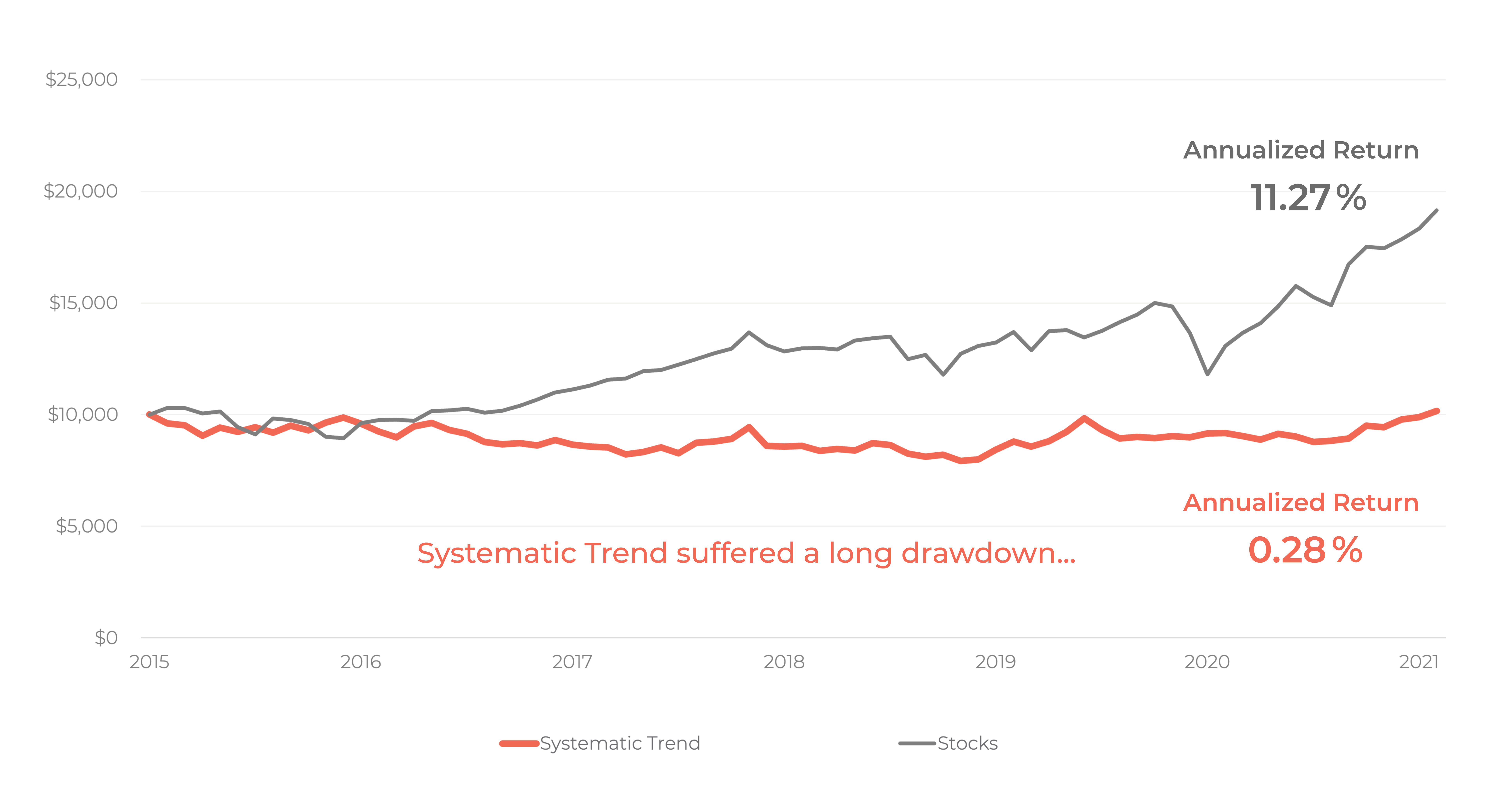

Global Equities vs. Systematic Trend: April 2015-April 20212

The obvious mistake many investors made during this stretch was to lose patience and punt the diversifying asset from their portfolios, thereby missing it exactly when it was needed. A more glaring and public version of this kind of mistake was made by the largest US pension fund, which abandoned its hedging program just weeks before the market chaos of early 2020.3

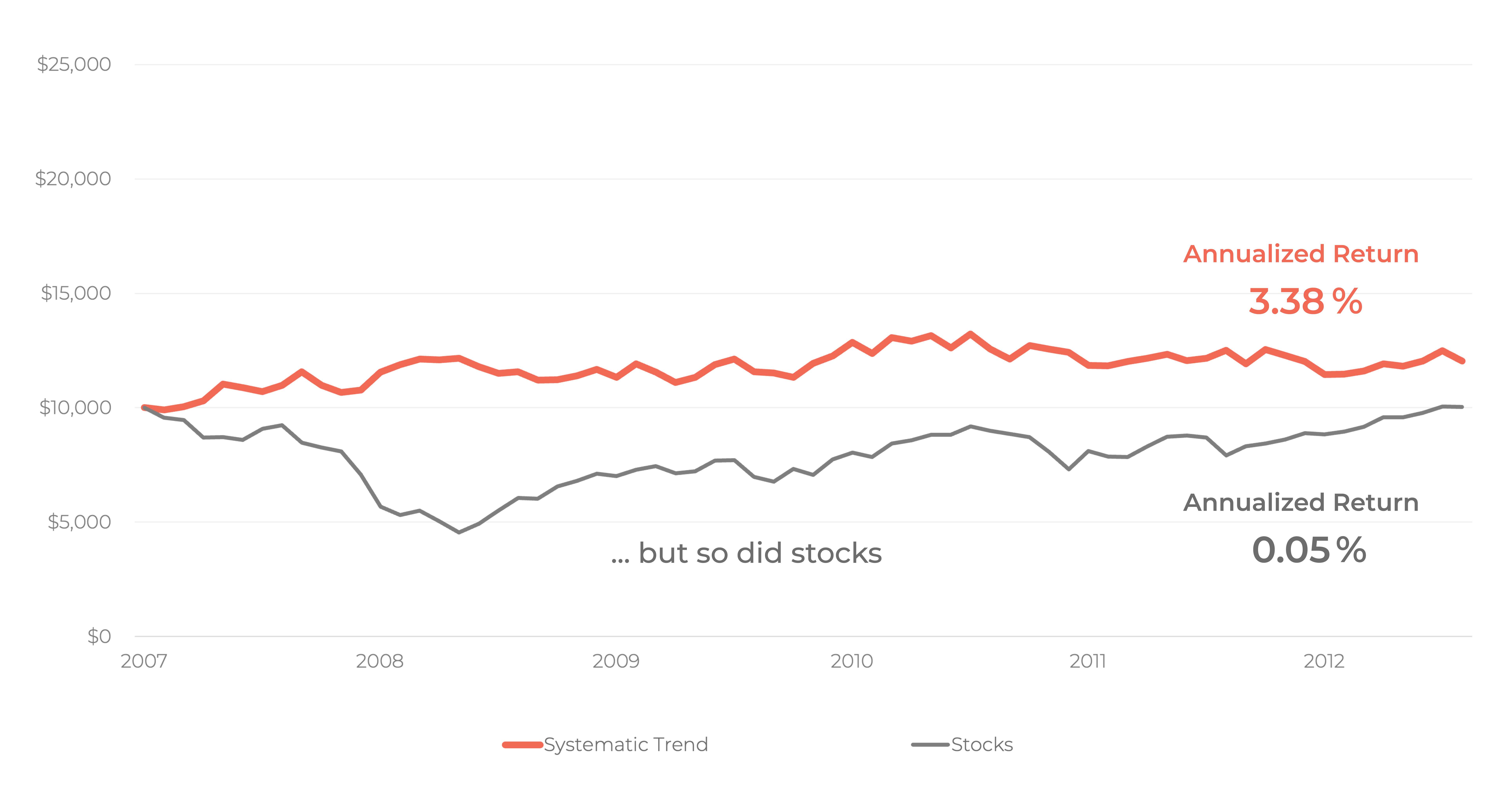

Of course, stocks have also suffered a long (and deep) drawdown this century--during which Trend held its own. No doubt many investors also sold stocks during the Great Financial Crisis. However, people find it harder to hold less familiar assets, particularly when they underperform the most closely-watched asset class. To take another example, many professional investors are unaware that gold has outperformed stocks since 2000, and very few individual investors own any.

Global Equities vs. Systematic Trend November 2007-May 20132

As advisors, we want to help clients bear the cost of diversification so they can reap its rewards. One way is to emphasize the purpose of thoughtful portfolio construction and show the benefit of each item to the portfolio as a whole. Beyond that, our toolkit includes a growing number of multi-asset funds that bring more diversification “in-house:” reducing the number of line-items that tempt investors to kick them to the curb when they underperform. So while we hesitate to call diversification free, we strive to drive down the cost to our clients, making it more comfortable to own a better portfolio.

1. Also referred to as Managed Futures, Trend Following, or Systematic Global Macro.

2. Source: Bloomberg, Portfolio Visualizer, Magnolia. Global equities are MSCI ACWI, bonds are Bloomberg US Treasury Intermediate Index, Systematic Trend is SG CTA Trend Sub-Index. Indices are not directly investable. Portfolios are rebalanced to original weights and the end of each year, and no fees or transaction costs are subtracted from the portfolio returns. Past returns are not a guarantee of future performance. Alternative investments like Systematic Trend may not be suitable for all investors.

3. CalPERS’ untimely hedge unwind

Disclaimer: The opinions voiced and information provided in this document is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered investment, financial, or legal advice. Nothing herein constitutes a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security or financial instrument. Magnolia Private Wealth does not provide tax, legal or accounting advice. Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. You should consult with a qualified financial advisor, tax professional, or other appropriate professional before making any financial decisions. The author and publisher assume no liability for any losses or damages resulting from the use of this information.

Insights from Our Team.