A Larger Pie

The secret to building a better portfolio is no secret at all. Better means a portfolio that adequately compensates an investor for the risk she bears. Better means improvements on conventional portfolios, which usually fail to meet this test. There is a better way: one well-grounded in academic research and validated by decades of practice. If it’s a secret, it’s been hiding in plain sight. We’ll return to the question of why it sometimes seems like a secret, but first let’s dive into why better is better and how to achieve it.

By conventional portfolios, we mean simple combinations of stocks and bonds. Most individual investor portfolios are some version of these under the hood–maybe more complicated on the surface, and usually more expensive. The standard assumptions the industrial-scale investment advice complex make are:

- A conventional portfolio can target a specific level of risk.

- An individual investor’s “risk tolerance” can be measured with survey questions.

- "Risk tolerance" can be used to identify the right portfolio for any investor.

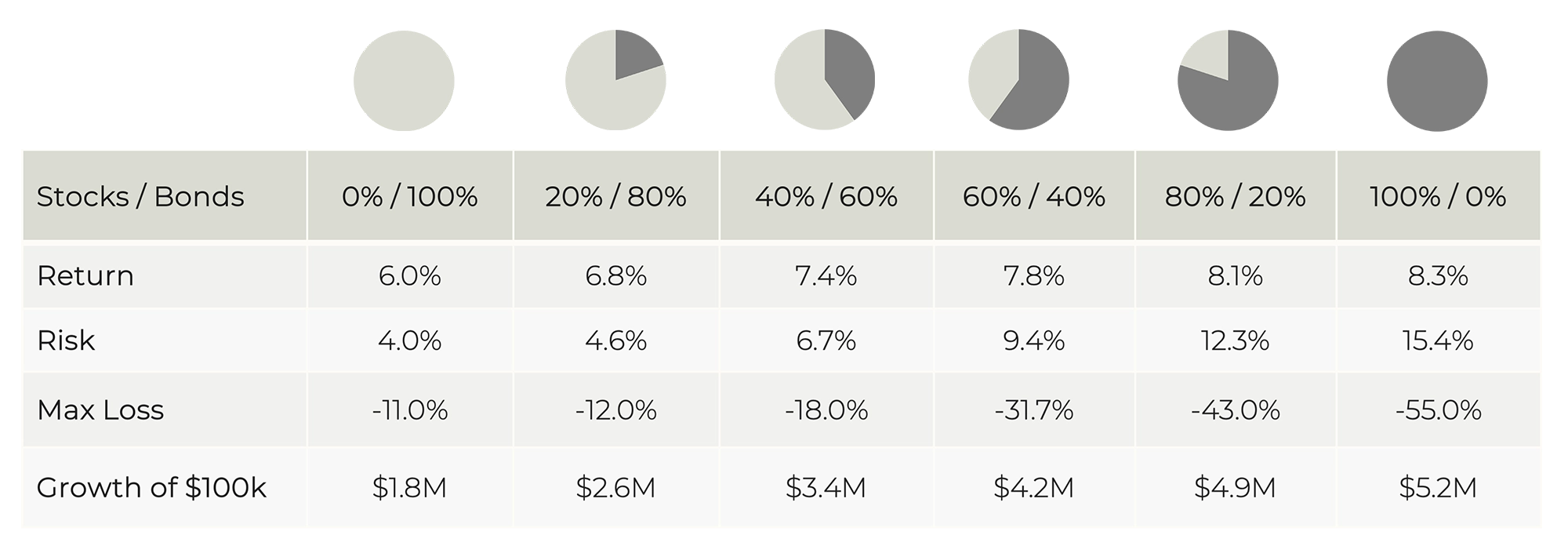

A typical menu will look like this1 :

We should emphasize the improvement over the bad old days of high-commission brokerages. The availability of these portfolios at low cost (and ease of implementation) represent a substantial advance in human well-being. Our hats off to the Vanguards of the world!

But we have quibbles:

- Even “moderate-risk" portfolios (like 60/40) can suffer losses that “moderate-risk” investors may find excessive.

- The lower returns that lower-risk portfolios deliver look smaller as annualized percentages than as dollars compounded over time.

- Risk tolerance isn’t an exact science: there’s a big difference between crashing a flight simulator and living through a plane crash.

- Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

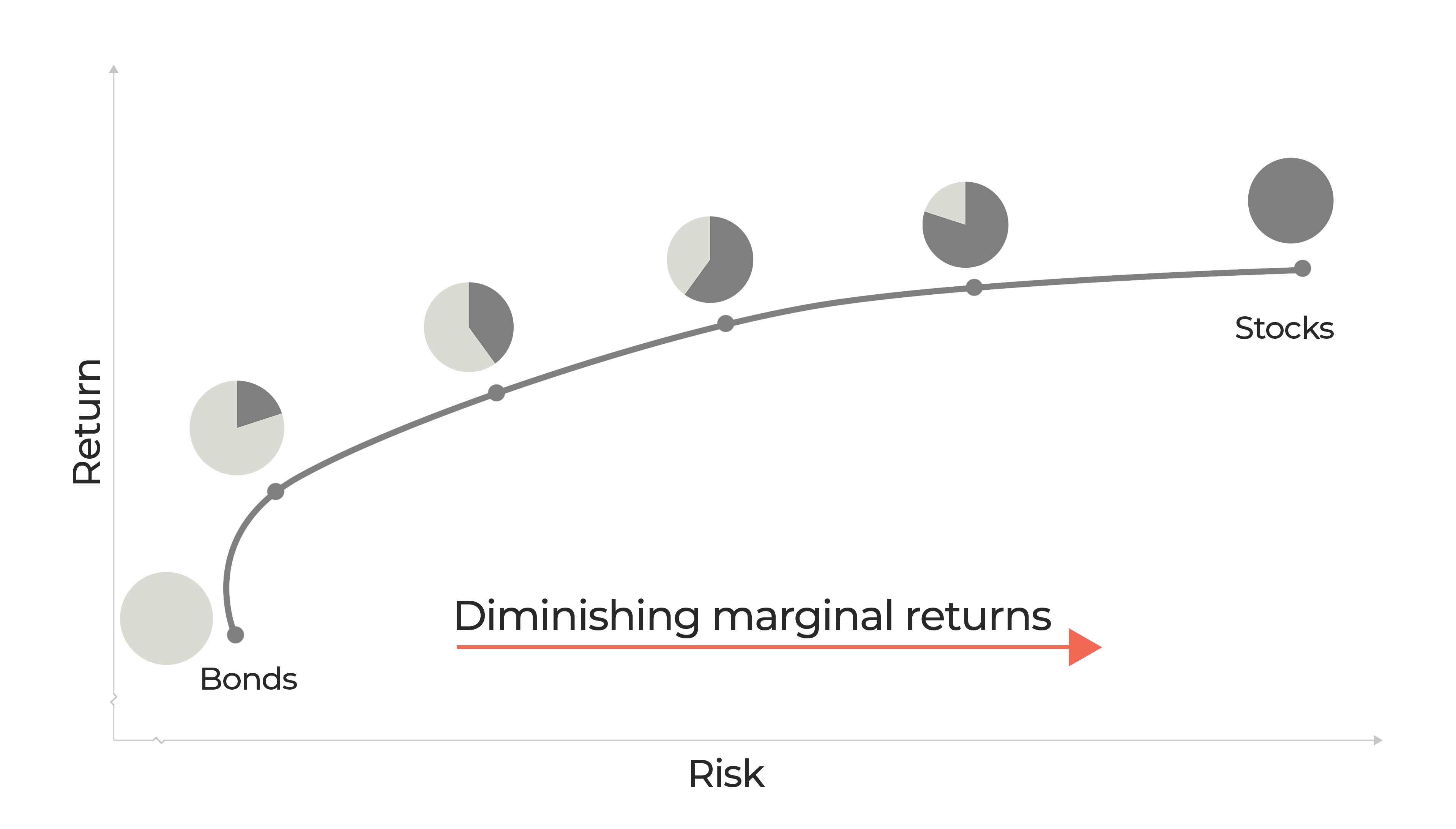

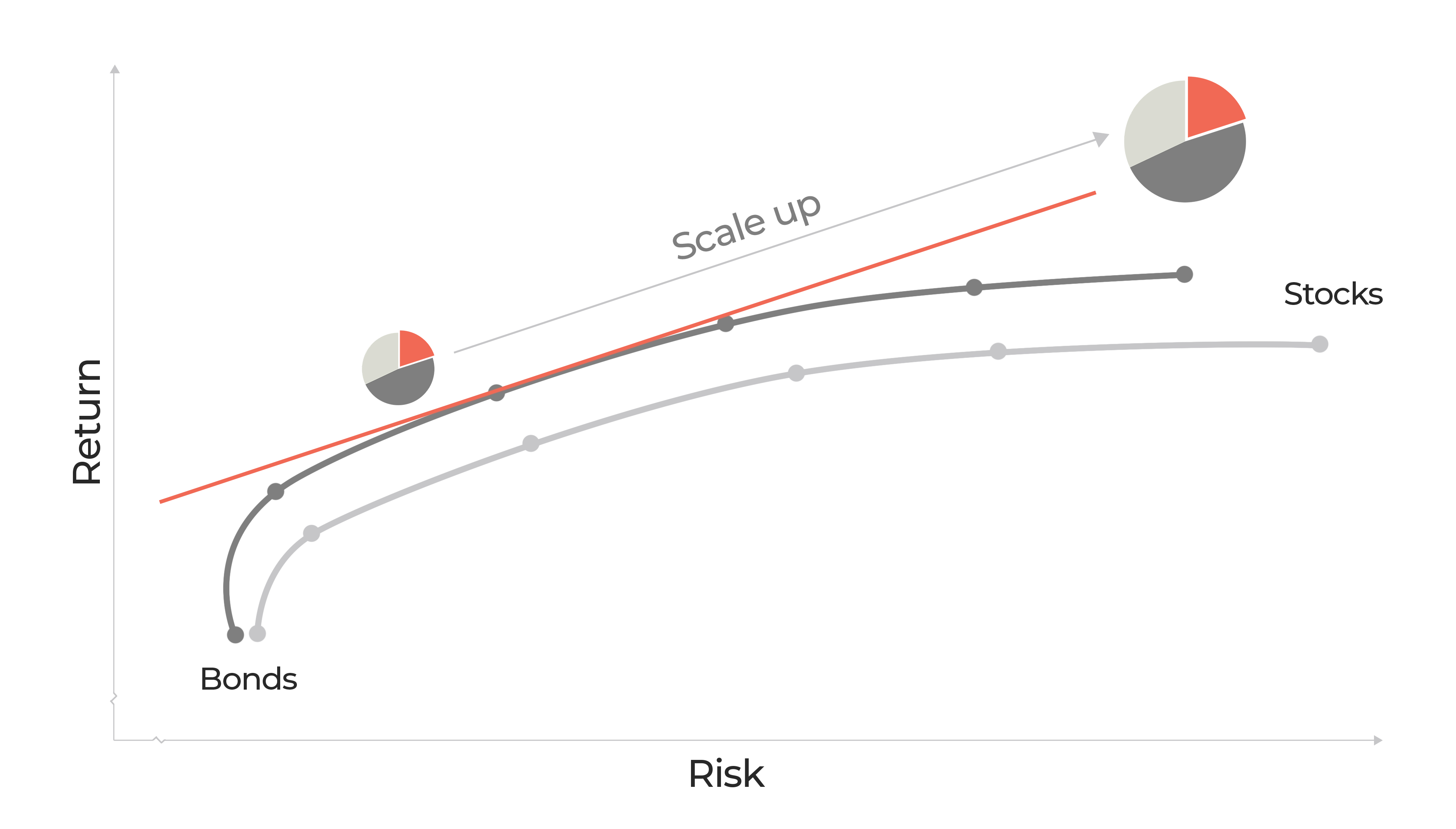

On the curve below2, each point identifies a different conventional portfolio of stocks and bonds. As we increase the allocation to stocks from left to right, the curve gets flatter and the investor receives less marginal return for the additional risk-–less “bang for the buck.” The portfolios also become less diversified: even in the “moderate” 60/40 portfolio, 95% of the risk comes from stocks. It’s a bad tradeoff.

A portfolio with a better balance of risks and the most “bang for the buck”is actually closer to 20% stocks/80% bonds. Many investors won’t be happy with this choice, leaving so much potential return on the table. It’s like having a car with great gas mileage but room for only one passenger and a change of socks.

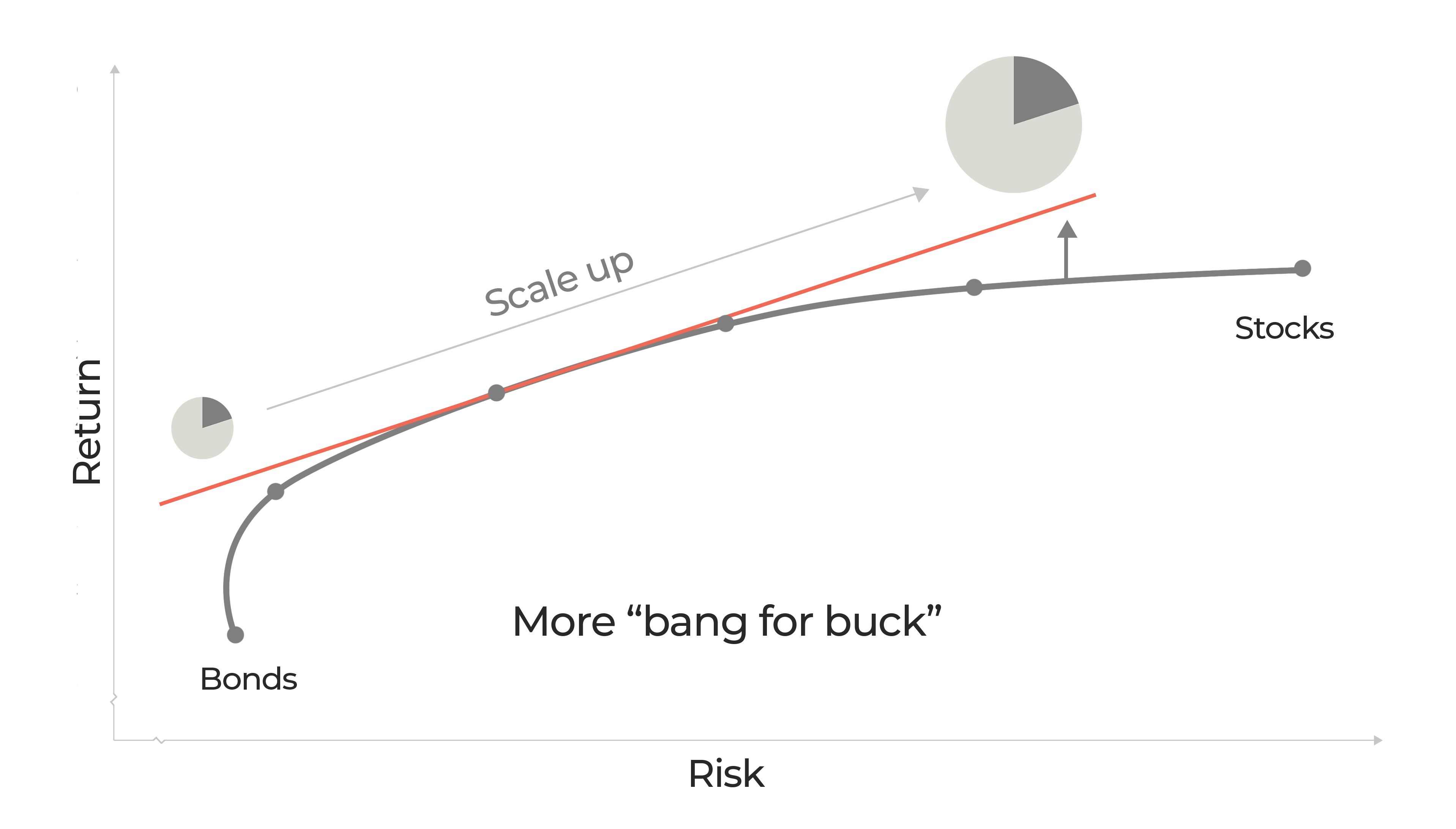

The trade-off is unnecessary: for starters, we could take a better portfolio and make it less risky by combining it with cash (a smaller pie). Or, we can scale it up to add risk and expected returns, making the pie larger. As illustrated below, this lets us choose among portfolios on the line, not the curve, and get more bang for the buck for any level of risk.

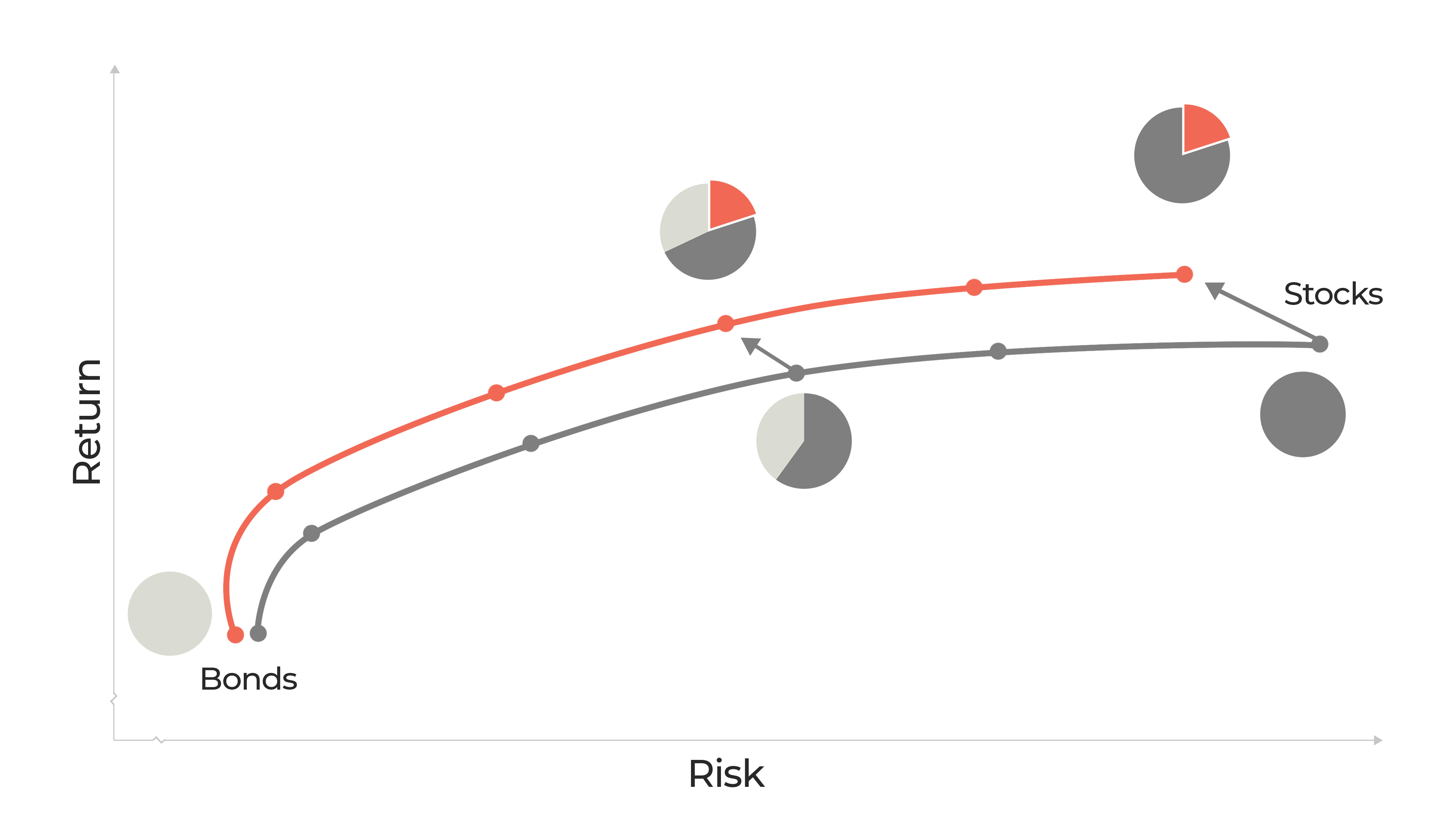

By adding other assets that reduce the risk of a the conventional stock/bond portfolio (by improving the diversification), we get more bang for the buck two ways:

1. A better pie with more ingredients: a more diversified multi-asset portfolio.

2. A bigger, better pie by scaling up the desired level of expected return (or to the level of tolerable risk).

Let’s pause for a moment to review we've accomplished:

- Diversification alone can reduce the risk of a portfolio and improve its expected return for the level of risk–more “bang for the buck.”

- However, it may or may not increase its expected return.

- We can address that trade-off by scaling.

- By scaling the better portfolio with prudent leverage, we can target our desired level of return, replacing a poor set of trade-offs with an optimal one.

Why doesn’t everyone do something like this? As it happens, many market participants do.

- Asset managers: to achieve their target exposures, can use futures contracts and be more efficient in their allocation of capital.3

- Family offices: borrowing against collateral (in the form of cash, securities, tangible or even business property) helps them achieve their desired asset allocation without encumbering key assets.

- Institutions and registered funds: modest cash collateral requirements for many futures strategies allows them to create overlays not dissimilar to the one we’ve illustrated above.

So why not everyone? Again, there’s no secret here. In fact, the general strategy is nearly straight from the textbooks and dates back to Harry Markowitz’s original work on portfolio optimization.4 It’s been developed, elaborated, and referenced by numerous Nobel Prize-winning economists. It’s far from obscure. There’s even a wealth of academic literature on why the strategy is not more commonly used, on topics like Leverage Aversion, Lottery Preference, and others. To many individual investors, the term “leverage” may imply excessive risk. Here we've shown how it can be used to lower risk.

There are caveats worth discussing which don't come from behavioral economics or institutional constraints:

- Diversification is essential: scaling up a risky asset simply magnifies the risk.

- Not all diversification is created equal: assets which are uncorrelated in benign financial conditions may not provide diversification when there’s stress in the market.5

- Scaling up requires leverage, which isn't always available at low cost to individual investors.

Did we mention none of this is new? Strategies like these gained popularity among institutional investors under the banner of “Portable Alpha”6 and have been deployed by the asset management giant PIMCO in their StocksPLUS mutual funds since 1985, which combine stock and bond exposures using futures–offering investors a larger pie.

For the broadest range of individual investors, the best way to achieve scale in their portfolios is inside funds that use futures contracts–professionally, responsibly and at the same low cost institutional investors enjoy–together with regulatory protections and often ample manager track records to validate the characteristics of the strategy.

Our clients can profit from a renewed focus on this old concept and a wave of new investment vehicles that implement it in a thoughtful way that are coming to market. Yes, it’s possible to have your (larger) pie and eat it too!

1. Source: Bloomberg, Portfolio Visualizer, Magnolia. Global equities are MSCI ACWI, bonds are Bloomberg US Treasury Intermediate Index. Indices are not directly investable. Portfolios are rebalanced to original weights at the end of each year, and no fees or transaction costs are subtracted from portfolio returns. Past returns are not a guarantee of future performance. January 1974-September 2023.

2. For illustration only. Underlying data sources available on request.

3. Made to Measure - Understanding the use of leverage in alternative investment funds

4. Markowitz, H.M. (March 1952). "Portfolio Selection"

5. Diversification Challenges

6. Why Is Portable Alpha Coming Back? Because It’s Working.

Disclaimer: The opinions voiced and information provided in this document is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered investment, financial, or legal advice. Nothing herein constitutes a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security or financial instrument. Magnolia Private Wealth does not provide tax, legal or accounting advice. Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. You should consult with a qualified financial advisor, tax professional, or other appropriate professional before making any financial decisions. The author and publisher assume no liability for any losses or damages resulting from the use of this information.

Insights from Our Team.